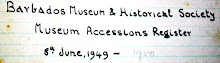

This year the Barbados Museum and Historical Society

(BMHS) celebrates its 75th anniversary having been

established in 1933 and opened to the public a year later

with a collection that had been amassed over several years

by the Rev. N. B. Watson, retired rector of St. Lucy Parish.

This collection has since grown enormously and the

BMHS now owns in excess of 250,000 items including

ceramics, decorative objects, paintings, prints and

photographs. Space does not permit all of these items to

be on display and it is the archives relating to the

collections that is the subject of scrutiny by our artist in

residence, Ingrid Persaud. She has made new artworks

based on her research in the archives. Some of these

artworks are juxtaposed with pieces from the museum’s

collections but she also brings into the museum space

some of the collections and archives of others who are

not normally considered producers of culture.

In Congo Index, she updates the portraits

housed in the Warmington Gallery. These portraits,

gifts to the BMHS, depict the owners of the Congo

Road plantation house, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Browne who

lived there in the 1890s. In 2008 it serves as the Hunte

family estate where several generations of the family live

together. The updating is done with an eye to the past

using similar lighting and setting, but rather than being

executed in oils, it is appropriately, for a century later, a

digital print.

Museums are only ever able to show approximately 5% of

their collections and the BMHS is no exception. What is

shown at any one time is the outcome of a complex

decision-making process of curatorial initiative,

conservation, space and funding. The Connell Gallery

decorative art exhibit of the BMHS no longer exists. It has

not disappeared but rather transformed and extended into

another kind of decorative arts exhibit – the African Gallery.

One type of decorative arts has been dismantled in favour

of another, which, while having a certain nostalgia, also

speaks to the preeminence of one culture over

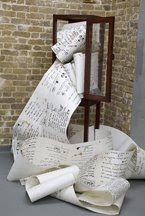

another changing with time. In No Remaining Evidence the

artist uses these “lost” objects to articulate a deep sense of

memory, loss as well as chart these changing times. The echo

of her voice through the gallery naming unseen objects

becomes a sort of memento mori. If the objects cannot be seen

they live on by being heard instead.

But the themes of loss, memory and death that pervade

archives are not allowed to overwhelm the space with

sadness. Indeed much of the rest of the work use the

devices of humour and play to explore these difficult issues.

In Hunters and Gatherers she invites us into the obsession

of collecting through a peek at the unusual collections of

ordinary people. It would appear that someone has

collected over two hundred fancy dress noses!

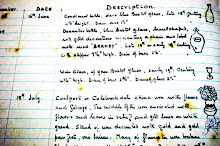

Archives Alive is a suite of etchings, each subtly

different from the other, that she has made using as her

starting point images representing the bookworm-eaten gift

receipt books that are over half a century old. The books are

ancient, they archive the past, yet they are also quite literally

alive. Just as the bookworms have eaten through the pages and

made their marks so too has the artist eaten away the copper

plates with etching needles and acid for her mark making.

In Utopia and Make Today History the artist presents her

own archives but they are of dust and diaries. Utopia, a

collection and “analysis” of dust gathered from the museum

galleries, calls into question the very notion of what, and

how, and why we continually classify what is within the museum

and the knowledge that is generated through these exercises.

Make Today History pushes this theme further through

a practical, web-based exercise of taking the power of

who collects, and what is collected, away from the

traditional custodians of culture to the man and woman

on the street. This democratization of the archive hints at

other models where spaces such as museums act as

zones where art intersects with a wider audience in a

meaningful manner. She even appears to invite narratives

on the role of an artist in residence at a museum.

In Residence provocatively shows the artist sweeping the

Museum. Is the cleaning a preservation of the status quo

or the ushering in of the new?

The show will be on from MAY 30 – JUNE 20, 2008

Private View: 29 May 6- 8pm

Barbados Museum and Historical Society

St. Ann’s Garrison

St. Michael BB14038

Barbados

T: +1 246 427 0201 / 436 1956

Monday – Saturday 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Sunday – 2:00 p.m. – 6:00 p.m.

Related Activities:

Seminar on the issues raised by the exhibition will be hosted by the 21 x 14 Art Collective, June 9, 2008 from 6 - 8pm.

Private View: 29 May 6- 8pm

Barbados Museum and Historical Society

St. Ann’s Garrison

St. Michael BB14038

Barbados

T: +1 246 427 0201 / 436 1956

Monday – Saturday 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Sunday – 2:00 p.m. – 6:00 p.m.

Related Activities:

Seminar on the issues raised by the exhibition will be hosted by the 21 x 14 Art Collective, June 9, 2008 from 6 - 8pm.

Thursday, May 29, 2008

Monday, May 26, 2008

NO REMAINING EVIDENCE

The two green platters you see below are from the Cornell Gallery which no longer exists in its original state having made way for the African Gallery. The collection is now largely in storage and is the inspiration for the sound installation No Remaining Evidence that you will hear in the art space.

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

HUNTERS AND GATHERERS

Below are images from the register of the BMHS collections which led me to make an installation about unusual collections and collectors.

Monday, May 19, 2008

CONGO INDEX

One of the pieces in the show is inspired by these two portraits in the Warmington Gallery of the Barbados Museum. They are of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Browne who lived at Congo Road plantation in St. Phillip.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

NOT ARCHIVES

Human beings have always collected. Indeed, Walter Benjamin claimed that every “passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories” . Some have found the passion overwhelming and have destroyed all their possessions such as Michael Landy in his piece Breakdown (2001). Our concern is with those whose passion for collecting has led them to delve into archives. There are several ways in which artists have engaged with archives. Some have created their own archives. Jeremy Deller and Alan Cane are doing just that with Folk Archive. Mark Dion has also created archives, for example, through his Thames Dig. Others such as Fred Wilson, Andrea Fraser and Susan Hiller have all intervened in existing archives. Our inquiry will be into what art is produced in the complex interaction of archive and artist. What links all the artists we are considering is that they are searching for modes of cultural criticism through investigations of and around archives. They have all in some way scrutinised the historical underpinnings of art, its production and its re-presentation. Their serious infiltrations unmask the myths surrounding systems of power in the art world. Indeed the dissection of the museum by artists has not only re-established the museum as a site of activity but also “reshaped the institution in permanent ways that will affect the ways audiences see collections in the future” .

Yet the very term ‘archive’ is problematic. Its simple dictionary definition is of “a collection of records of an institution, family etc…a place where such records are kept” deriving from the Greek “arkheion , repository of official records” . The arkheion was originally the residence of the archon or chief judge so archives were literally the documents that were preserved (and later interpreted) by the judges. Archives were therefore privileged documents, accessible to a few, who in turn, as keepers and interpreters, determined the public significance of the documents. Already we note that there is a distinction between the materiality of what constitutes an archive and the use that is made of it – a point we return to later.

The attraction of the materiality of an archive is that it promises a complete, inclusive, authentic and authoritative collection of data on a given subject. In a world of continual chaos it is the embodiment of a desire for uniformity and control. It is about removing something from use and the vagaries of time thereby preserving it. Each archive allows us to self-reflexively create a history and there is the danger that sometimes the archive mummifies objects or data in time. The archive forms a silent body of knowledge that waits, like Sleeping Beauty, to be kissed and brought to life through later use. Defiance of this fossil-like quality of archives is attempted by never-ending projects such as the African and Asian Visual Artists Archive . This project is termed a ‘living archive’ to contradict any quest for authority.

Archives are about remembering - of saving something from the dark hole of time. But they are not only about the past; interpretation can help us make sense of the present and forge the future. At its most progressive, the archive jolts re-interpretation of the present. Walter Benjamin suggests that to “articulate the past historically does not mean to recognise it ‘the way it really was’. It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger” . In keeping with this notion that the history contained in the archive is that which “flashes up at moments of danger”, Foucault, in his work, The Archaeology of Knowledge, considers the archive as part of a continuum somewhere between the language in which artists operate and the corpus which is the body of work produced. It becomes a machine generating social meaning where meaning and truth are never stable. He states that,

The archive cannot be described in its totality; and in its presence it is unavoidable. It emerges in fragments, regions, and levels, more fully, no doubt, and with greater sharpness, the greater the time that separates us from it.

And later,

The analysis of the archive, then, involves a privileged region: at once close to us, and different from our present existence, it is the border of time that surrounds our presence, which overhangs it, and which indicates it in its otherness; it is that which, outside ourselves, delimits us.

The archive, built around the notions of loss and emptiness, is the re-presentation of loss and desire. Yet it can be of help in charting the shifting patterns in the ‘border of time’ surrounding our existence. It assumes a crucial role in our understanding of how and where the transitions and ruptures in culture take place. Archives present the opportunity to construct, de-construct, interpret and re-interpret endlessly, in the light of the present, and in contemplation of the future. No archive, no past, and, potentially little future. According to Stuart Hall the activity of archiving is always a critical one. Since archives are in part born out of cultural power and authority they are, always “open to futurity and contingency in the relative autonomy of an artistic practice; always an interruption… which is to enter critically into existing configurations” . For him it is about prising open the closed structures into which archives have ossified.

The archive is at best a complex myth. It contains inherent contradictions. Creation is simultaneously bundled with suppression and repression. This choice of suppression and repression may be quite unconscious. The archive’s beginning is an arbitrary one so it is never the beginning it seeks to be nor is it ever the ultimate it desires. Far from being authoritative, archives can become a burial site or a cistern into which material is flushed. The archive is an unfulfilled (and impossible) promise that is forever being translated by its keepers and its users. Derrida, in his work Archive Fever believes that the meaning of the archive can only be known in the future and even that is not guaranteed. He finds that a “spectral messianicity is at work in the concept of the archive and ties it…to a very singular experience of the promise”. The archive in Derrida’s terms is an unreliable and of necessity idiomatic character which is “at once offered and unavailable for translation, open to and shielded from technical iteration and reproduction.” The unreliability of the archive can be undermined by those creating it and by what is subjectively included. One has only to consider the role of gossip, for example, in the creation of Andy Warhol’s archives to realise the fluidity and unreliability of using them to ascertain any sort of “truth” .

Museums are the key repositories of archives of culture. But it is not just any culture. Through the complex inter-relationships among patrons, curators, administrators and artists, museums have always been vanguards of the traditional status quo. They archive what, as elite culture-creators, they consider should be legitimised as part of our cultural capital. That the museum is held out as the ultimate custodian of history is spelt out by the key figure of Alfred Barr, the first Director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, in a confidential report where he writes that

the Museum “produces” art knowledge, criticism, scholarship, understanding, taste…Once a product is made, the next job is distribution. An exhibition … [c]irculation of exhibition catalogues, memberships, publicity, radio, are all distribution .

The crudity of this statement may be function of Barr’ role as a pioneer in attracting private money to fund his museum but it also raises the more interesting question of the commodification of art that informs archives. When art is equated with any other commodity that is bought and sold according to market forces then it is these market forces that inform what is worth archiving from museum’s viewpoint.

When museums set themselves up as the arbiters of taste they ultimately force the creation of insiders and outsiders. The issue of what is at stake in when there is Pierre Bourdieu has taken on board an insider/outsider view of culture. He argues that the love of art is made a mark of the anointed few which in turn allows “museums [to] betray their true function, which is to reinforce for some the feeling of belonging and for others the feeling of exclusion”. Others see museums as sites of greater possibilities. James Clifford, in his book Routes suggests that it is useful to think of museums as, “contact zones” a term he borrows from Mary Louise Pratt’s book Imperial Eyes: Travel and Transculturation . The expression “contact zone” runs counter to the notion of a frontier that evokes separation between subjects. Rather than separation, a contact zone perspective speaks of “how subjects are constituted in and by their relations to each other” and emphasises “copresence, interaction, interlocking understandings and practices, often within radically asymmetrical relations of power” . Clifford translates this into the museum context where the collections become live relationships of a historical, political and moral nature and where they are a “power-charged set of exchanges, of push and pull” . In this model “a center and periphery are assumed: the center a point of gathering, the periphery an area of discovery” . Were we to open up museums in this way, to both contestation and collaboration, it may be possible to rework relationships so that the diverse agendas and varying requirements of the museum’s “publics” are brought to bear on the displays.

The artist Fred Wilson, acutely aware of the insider/outsider issue yet open to the possibility of the museum as a “contact zone”, chooses to use the museum’s archives as his laboratory. His work reveals what is made invisible by the visible museum displays and exhibitions. If archives are a way of remembering they are also a way of forgetting. We have no memory without the archive so we can never measure the losses they conceal. In works such as Mining the Museum, The Other Museum, and Installation at Seattle Art Museum, Wilson uses the visual tactic of three-dimensional montage to articulate what he sees as the hidden and silenced narratives of museums. When asked about his aesthetic preoccupation with the museum Wilson replied that it “ is there that those of us who work toward alternative visions receive our so-called ‘inspiration’. It is where we get hot under the collar and decide to do something about it.” What Wilson set out to do is discover the extent to which material is buried in the Society’s archive and the extent to which this ossification represses or suppresses other narratives.

In Mining the Museum he re-presents these silenced archives of the Maryland Historical Society to explore the specific history of that institution. The title is very tongue in cheek alluding to mining for gold, exploding land mines “or it could mean making it mine” . His methodology consists of making “use [of] the whole environment of the museum as my palette, as my vocabulary…and try to distil it and re-use it [to] squeeze it of its meaning and try to reinvent [it]. The Maryland Historical Society had been set up with a mission statement that required the collection and preservation of material in relation to the state’s history “in reference to any remarkable event or character, especially biographical memoirs and anecdotes of distinguished persons” including histories of “colonisation, slavery and abolition” and “any facts or reasoning that may illustrate the doubtful question of the North American tribes”.

As curator and creator of this site-specific installation he does a number of interventions that are often subtle but startling. In one room for example, there is a “Truth Trophy awarded since 1922 for Truth in Advertising” which sits among six pedestals. On one side there are the busts of Napoleon Bonaparte, Henry Clay and Andrew Jackson and on the other side three empty pedestals labelled Harriet Tubman, Benjamin Banneker and Frederick Douglass. The irony of course is that the invisible busts are of the people with a real connection, and who made a real contribution, to Maryland. In another part of the exhibition Wilson shows a fractured painting of a white man called Henry Bebie, which is lit from behind by videotape of a black man who tells his story as the son born out of the rape of an enslaved mother. Move through the exhibition to the section on “Metalwork 1793 – 1880” and you will find repousse silver. You will also find slave shackles. Look at the work in “ Modes of Transport” and you see a beautiful antique baby carriage. Tucked inside the pram you look for baby blankets to cover the little one. But the little one’s blankets have been replaced - with a Ku Klux Klan hood. Nearby photos show black nannies pushing similar baby carriages. The juxtaposition is both surprising and shocking.

What is really audacious about Wilson’s work is that he does not bring outside material to illustrate his concerns about gender and race. Rather, the explosives are fashioned from the museum’s own archives and sited within the geographical boundaries of the museum. Yet the bombs that are detonated are not intended to oust one history simply to substitute it for another (subjective) one. Wilson suggests that in Mining the Museum

I’m not trying to say that this is the history that you should be paying attention to. I’m just pointing out that, in an environment that supposedly has the history of Maryland, it’s possible that there’s another history that’s not being talked about. It would be possible to do an exhibition about women’s history, about Jewish history, about immigrant history based on looking at things in the collection. I chose African American and Native American information because it was impossible for me to overlook. But it was never to say that this was the history you had to be looking at.

In a sense it does not matter whose history is being placed or even displaced. What is essential is that Wilson has engaged with the museum and its archives in a way that secures that it has lost whatever innocence it possessed. To this extent, as a work of institutional critique, it succeeds. What is at stake is nothing less than the portrayal of the exotic other. By subverting the existing taxonomies he defamiliarises what has been taken for granted. He makes the invisible relationships within museums startlingly clear. Wilson continues to do this in more recent work such as In the Course of Collection at the British Museum , which included display mounts, and labels that the British Museum has used from the nineteenth century to the present day. By charting the move from visible to invisible supports, and from hand-written to printed labels, the artist tries to expose the museum’s desire to appear impartial and impersonal. The extent to which the museum really believes that it presents an objective view from its archives is unclear but at least Wilson’s work unsettles any complacency regarding this issue.

Looking at the museum from inside its hallowed walls runs several risks. One of the difficulties is that projects of the museum looking at itself or the artist looking at the museum is that they have become an art genre of their own capable of being recouped and neutralised by the white cube. Works by Mike Kelly (The Uncanny), Marcel Broodthaers (Musee d’Art Moderne, Department des Aigles (1968-72)), Ilya Kabakov (Incident at the Museum, or Water Music) and Christian Boltanski (Inventory of Objects Belonging to a Young Man from Oxford) to name a few, have all contributed to a critique of the value systems embedded in the museum and the extent to which they address contemporary issues. By creating fictional museums they expose the politics of the archives of art that are museums. Yet the problem remains that it is the institution requesting the critique by commissioning the artist to do the work. The institution therefore defuses the criticism by providing legitimacy for the artist. Thus, “artwork that laid political and ethical landmines to explode the ideological apparatus of museums is often defused” . Yet in spite of the fact that the war with the museum seems to be going against the artist what is crucial is that the battles continue to be fought for therein lies the essence of the evolving culture.

While the museum has found ways to defuse the bomb of institutional critique this has not stopped artists from trying to plant them in unexpected and innovative ways. It is precisely this kind of unexpected and unique approach that we have come to expect from the performances of artist Andrea Fraser. Her works include performances in museums as well as galleries and private corporations . Like Fred Wilson she uses irony to great effect. However, her real strength lies in searing satire. To understand this better you have to take one of her museum “tours”. She has produced “tours””, for example, as part of the New Museum of Contemporary Art’s Damaged Goods: Desire and the Economy of the Object (1986) and later at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1989). In both works she assumes the persona of a docent, Jane Castelton, a prim, suited and bespectacled woman who lead groups on tours of highlights of the museum - just do not expect to be shown just the art works on display. The New Museum tour starts “normally” where she introduces herself as Jane Castelton and explains that

My goal as a docent at the New Museum is to provide you with an enjoyable, perceptive experience with our art objects…. The New Museum started its docent program because, well, ah, to tell you the truth, because all museums have one. It’s just one of those things that makes a museum a museum. And, like other museums, ah, most of them anyway, the New Museum doesn’t pay its docents. The docent staff is a volunteer staff. We don’t do it for money, we do it because we like to…

After this slightly curious start it soon becomes clear that this is no nice lady tour guide and that this will be an extraordinary guided tour. Fraser/Castelton does not draw attention to the art works as might be expected of a docent. Instead people are taken to the museum gift shop, lectured on the security system and made to linger by the ladies toilet. We join Jane Castelton outside the Ladies Room where she is speaking to her group:

The consideration of material support in this work, with its brilliant appeal to the contextual function of the image, undermines, ah, really undermines the artwork’s traditional claim to autonomy, to transcendent meaning or truth. This particular image – as those of you who are familiar with so-called international symbols may already know – is supposed to represent a woman…In this sense, it can be situated in a tradition that stretches from the prehistoric Venus of Willendorf to the painting of Willem de Kooning.

These scripts are a seamless mixture of excerpts from the archives of museum documents as well as the artist’s own words. So, for example, when Jane Castelton leads groups of anyone who will follow her around the Philadelphia Museum of Art we are treated to a similarly bizarre mixture of the official voice and the subversive Castelton script. We join Jane in a period room entered through a narrow corridor also containing a door to the Men’s Room. She uses this as an opportunity to read from documents in the museum’s archives reflecting on cleanliness and its relation to social order:

On this side of the wall is a family inclined to dirt and disorder because of its unperfect social education…. Cleanliness of persons or rooms is wholly forgotten… The rights of property are disregarded or are only respected through fear and personal force. On the other side of the wall only a few inches away, the floor, neatly carpeted, is spotless. It stands to reason that slovenly and destructive occupants are not accorded the same attention that is given to…those who are clean and careful and prompt in their payments.

The discourse above moves through the official to the suppressed, other discourses, that inform archives. Art may be the starting point but it is not the end game. We are confronted with socio-economic issues related tangentially to the art objects that in turn raise questions about the structure and narrative of museums. This is complicated by the persona of Jane herself. Part academic, part ideal visitor, we are never able to place this hybrid into a convenient slot. Fraser, when asked what she wants of Jane, states that,

As Jane Castleton, I articulate what the museum wants. But against this museum discourse, I want to introduce what Jane wants, what I want: specifically, the point at which it exceeds what the museum promises, or takes it too literally, or takes herself as its object. The split between her discourse and the museum’s is conditioned on her position in the institution: as a woman, as a non-expert, as a volunteer – not a high level patron. This split is a wedge I hope to introduce into the chain of identifications, visitor/ docent / bourgeois patron – and what I hope distinguished my performance from an ironic re-presentation of institutional discourse.

Fraser’s choice of the docent is a clever device that facilitates her goal of revealing the layers of insecurity that permeate the museum. Creating culture through a process of inside/outside, by holding itself as the modern day version of the archon, lays bare the uncertainty and fragility of the institution and those who are part of its apparatus. It is precisely Fraser’s lack of authenticity that suggests the underlying crisis within the museum.

When not actually conducting tours herself you might find the artist on an audio tour. For the 1993 Whitney Biennial she constructed an audio tour focusing on the personnel behind the museum – the curators, director and education staff. The tour consisted on hearing answers to questions Fraser asked of the staff – but not her questions themselves. Fraser’s questions invite responses relating to the values of the museums, its aspirations and its ideal visitors. It is the ultimate gossip tour. The listeners are given a chance to hear what the museum really thinks of them. This museum voice is an uncomfortable one and it was Fraser’s intention to “not only represent the speaker’s anxiety but to confront the viewers with their anxiety.” Here Fraser again confronts the insider/outsider dichotomy involved in ideas of art connoisseurship.

She continues to make interventions in museums as in MoMA’s Museum as Muse (1999) but also in bookstores such as Bibliomania (at Waterstones, UK,1999) and galleries such as the Galleries at Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia (1997). Her video work Inaugural Speech (1997) was included in the exhibition Visual Worlds (2001) at the Richard L. Nelson Gallery in California. Fraser is always forcing us to confront our desires and collusions within systems of power. One critic summaries that at her best she “forces to consciousness the tacit affiliations and disavowals that structure our relations to the institutions of art” . She makes us sceptical of officialdom and “fosters a critical awareness of what we want from these institutions, and maybe more important, what they want from us” . Fraser succeeds in exposing the vulnerability of curators and educators whose existence is predicated on mere reputations of insider connoisseurship. She also confronts us with the issue of the commodification of the art object. The scripts in her “tours” highlight the obsession with market value of what is “art”. Then, by refusing to create objects, her works exist only as recorded performances that resist easy categorisation for the marketplace. This resistance, on so many levels, opens up the possibilities of a contact zone so that it is harder for museums to speak with a singular, authoritarian voice. Ironically, it is by taking on the singular, authoritarian voice of a pseudo-expert that she undermines these notions of connoisseurship.

Both Wilson and Fraser, in different ways, assumed the persona of experts of museological systems in order to engage those systems according to their own rules. However, it is perhaps in the work of Mark Dion that we see the world of possibilities that this methodology offers. In works such as Raiding Neptune’s Vault: A Voyage to the Bottom of the Canals and Lagoons of Venice (1997/ 98) and Tate Thames Dig (1999) he assumes a persona somewhere between archaeologist and ethnographer – even dressing in a white scientist’s coat. In Raiding Neptune’s Vault, a commission for the Venice Biennale, he dredged a small bit of a Venice canal. Stage two involved the dredge being sifted and catalogued. The results were displayed in cabinets next to the ”laboratory”. In the latter two stages the public were invited to observe the processes.

He builds on this in Tate Thames Dig by taking the archaeologist analogy further. Dion and his team had two sites for the dig corresponding to the banks of the Thames near Tate Britain and further along at the site of the new (and then unopened) Tate Modern. Tate Thames Dig divides into three, equally important stages. In the first the banks are combed for detritus. Their neon-coloured jackets, of the kind used by officials, easily identify the team of “experts”, although they are just members of the local community. Each “scientist” chooses what random bits should be retrieved. Members of the public are invited to observe the scientists at work. Phase two finds them in white overalls under pitched tents on the lawns of Tate Britain. You could be forgiven for thinking that you had been whisked back in time to the scene of some nineteenth century expedition. Under the sun, Dion and his team sift, clean and catalogue the “finds” and allow members of the public to both observe and ask questions. Phase three sees the results of the dig displayed in a huge, specially built cabinet in the Tate gallery.

Dion’s work exposes the problems of taxonomy. The arbitrary nature of all sorts of hierarchies is called into question. Who collects the archive material, how it is classified as well as what and how it is displayed, are all called into question. Is this a scientific exercise or an excuse for one? The artist and his team certainly look the part and appear to be engaged in activities that resemble a committed archaeological expedition (albeit one belonging to an earlier century). The eminent archaeologist Colin Renfrew finds that in this work art does challenge his discipline. He considers that

The Tate Thames Dig is …too thorough to be dismissed as mere counterfeit endeavour, too meticulous to be seen simply as play…it does recapitulate the archaeological process. It subjects that process to scrutiny. It partakes in the immediacy of contact with the past through the material remains, the finds, which archaeology yields up. It puts it on display.

Dion makes us question the boundaries of the real and the counterfeit. Archives exist to fulfil our longing for authority but Dion makes us take issue with the authority that we bestow on them. We are also made to confront that eternal question of what is art. He does not create an easily commodifiable art object since the process of making the work is the art. Within the making of the work he also makes others question what is the essence of their discipline – in this case archaeology.

Ideally, the ethnographer would be producing knowledge. What knowledge is being produced here? Critic Joshua Decter believes that Dion’s work is compelling because of “the way in which a specific process is employed as an allegory for a more generalised understanding of the relationship between museum curators, dealers, historians and restorers” . This is a game of manipulation with an eye on the writing of narratives.

However, by borrowing the trappings of a nineteenth century scientist engaged in fieldwork in some hot, exotic land Dion raises the question of the coloniser. Now the artist is exacting revenge on the museum that has traditionally been his master. Coles discusses this aspect of Dion’s work and finds that although”[o]nce colonized by the museum, the artist now appears to colonize the colonizer” . One colonizer is much the same as the next and this must be the most troubling aspect of Dion’s work. Indeed, Dion admits that he has “at various times become the museum taking on the duties … [p]ersonifying the museum…” . Contrast this with Wilson’s statement quoted earlier that there are many histories in a museum and no one has the authority to mark their history as the defining one. Dion falls into the trap of replacing the museum with the revenging artist as the final arbiter of culture.

Some, like Joseph Kosuth, would argue that in spite of these failings the artist is still often best placed to act as anthropologist. For Kosuth because the anthropologist is outside the culture he studies the task of anthropologising one’s own society becomes impossible. The artist by contrast is attempting to gain cultural fluency in her own culture and her success is understood in terms of her praxis. For Kosuth “[a]rt means praxis, so any art activity, including ‘theoretical art’ activity, is praxiological” . In the artist-as-anthropologist model he is suggesting that since the artist is mapping an internalising of her own culture through her art- making, then she can succeed where the anthropologist has always failed.

By contrast Hal Foster warns against artists falling into the trap of ethnographer envy. In his essay The Artist as Ethnographer he argues that the path of artist as ethnographer is strewn with obstacles – some of which we have already noted. He alerts us to the problem of projection in the participant-observer model adopted by ethnographers. He also believes that this kind of work plays to the myth of the redemptive artist. Most damning of all is the manner in which whatever critique is made by the artist becomes internalised by the institution either as a show of tolerance or inoculation. This stems from the ambiguity of the deconstructivist positioning of the artist. By simultaneously placing oneself both inside and outside the museum the artist (and the museum) can lapse into duplicity. Foster considers that in “the face of these dangers – of too little or too much distance – I have advocated parallactic work that attempts to frame the framer as he or she frames the other” .

The act of framing, while simultaneously being framed, which Foster refers to, may be illustrated by work such as Susan Hiller’s From the Freud Museum (1991 –96). The piece consists of fifty specially made archaeological boxes in a vitrine and harks back to an earlier version of the work made during a residency at the Freud Museum. Each box contains some mixture of text, image and artefact and all are titled, dated and captioned. For example, there are boxes called Nama.ma (Mother); Chamin’ha (House of Knives) and Sophia (Wisdom). Most of the objects displayed are personal to the artist – talismans, mementoes or banal relics and all are presented to us as some sort of “archive of misunderstandings, crises and ambivalences that complicate any notion of heritage”. The evidence of Hiller’s “dig” has left us with fluid taxonomies that reference art, archaeology and psychoanalysis and frames her even while she frames it.

Even if Foster’s concerns were met through work such as Hiller’s there are still some troubling issues remaining. Certainly this type of art is consistent with the self-reflectivity of postmodernist art. Yet there is something uneasy about the ease of using the archive as a medium or indeed making it the art commodity itself. In a sense conservative institutions like museums are the easiest of targets presenting the liberal- minded artist with a ready-made set of outcomes possible with each dig into their archives. Indeed, there is some recognition of that already in work such as Mike Kelly and Tony Oursler’s The Poetic Project 1977 – 1997. This is a collaborative work in which the artists document their history together as performers in a group called The Poetics. Instead of material from the past we get almost entirely new material created out of sketchbooks and audio recordings from the early 1970’s. In short the work is a fake. The real archive is of their present collaborative efforts and ironically calls into question how history is made and re-made. Diane Shamash, in her article “The Strategic Archive” points out that these archive-based works are being subject to market and institutional pressures that restructure the archive as an “art experience…carefully manufactured and packaged, [where] artists and curators are creating archives which function as commodities .

One model that takes us beyond this commodification and even the kind of art that Hal Foster’s critique envisaged, would be the work of artists Jeremy Deller and Alan Cane who have created Folk Archive. This is an on-going project presented recently at Tate Britain’s Intelligence – New British Art 2000 exhibition. Deller and Cane have set up the structure for an archive and invite the public to fill it. They have a Post Box and a web site for receiving information about potential archive material and their stated aim is to

highlight and preserve some of the undervalued cultural production of individuals in the face of the increasingly aggressive consumer society we inhabit, and [to] investigate how this production may be adapting to a rapidly changing world.

The artists have travelled around the UK seeking out and documenting what they define as the raw creation of culture that takes place in, for example, pubs, villages, and clubs. These are not normally places accorded the status of institutions of high culture. Yet they are sites for recording major events such as births, marriages and deaths. The artists have investigated these sites and recorded the work of highly skilled amateurs who are producing fascinating and often intricate objects that belong to a time capsule oblivious of changing trends and tastes. The folk art they found reflects the traditions of local communities where skills, crafts and myths are handed down from one generation to the next by practice or oral tradition.

To date the Folk Archive also includes some very unusual events that are overlooked by the mainstream culture machines grinding away in urban city centres. For the Wray Scarecrow Festival at the end of April every year, the whole village makes scarecrows on different themes. The care and irony with which these are crafted is illustrated by the Jimmy Saville Scarecrow made by Jilly and Graham Whitely which tunes into the trademark characteristics of the TV personality and is instantly recognisable. Perhaps for me the most memorable record of the Folk Archive is the Crab Fair of Egremont . The men participating go to great lengths to contort their faces to look as crab-like as possible. The Crab Fair is a deadly serious annual affair and some (including the reining champion) have even gone as far as having several teeth extracted so that the perfect “crab face” could be created. This does not seem that far off from the “high culture” art of someone like Orlan with her numerous plastic surgeries! The breath of the Folk Archive extends to include floral arrangements made by womens’ groups; the World Conker Championships and sexual images made using the keypad of a mobile phone and distributed as text messages. There are numerous intricate craft items including a tiny car and house made entirely from household sponges. The miniature car is a very specific, and identifiable model of the Mini created by BMW and is detailed down to the windscreen wipers and BMW logo.

The Folk Archive is an alternative vision of culture. It is filled with material from and of ordinary people. These folks have not been legitimised by the sanctity of museums and galleries. In this sense the materiality of the Folk Archive stands simultaneously within and without the museum framework. That it was shown at Tate Britain does not mean it has been recouped by the museum. For the moment they sit together in queasy silence. It is clear that the work is critical and serious but its source material remains an area that the academic art world is insecure about.

Deller is an artist who wholeheartedly embraces popular culture in making critical work about the manufacture and legitimisation of culture that does not slip into spectacle. He is in the throes of a love affair with ordinary not elite culture. David Beech in his essay “High on Good Shit: Towards an Ethical Relation to Popular Culture” suggests that Deller is not a coloniser of popular culture but rather betrays in his art “a decisive uncertainty”. Although he is most definitely serious about art and popular culture it cannot be said that he sacrifices art for easy entertainment. Further, Deller is “not guilty of parading popular pleasures for the genteel perusal of the art lover. His uncertainty recommends him . There is no scientific rigour to Deller’s archive nor can it be easily verified or commodified. This most modern of artists has created an archive that is resistant to the idea of the authority of the archive and to this end his work is more complex and thoughtful than those who have sought to replace the institutional authoritative voice with a claim for power by the artist.

The archive as an art medium is now firmly established and, as we have seen, a fairly reliable method of exposing issues such as justice, power, race, sexuality and gender. However the relative ease with which this expose has been achieved will become much harder. In Deller and Cane’s Folk Archive we are made to contemplate alternative sites of culture creation including the internet. The technology of the internet embraces speed of information both in its reception and transmission and thus undermines all attempts to ensure archives are authoritative and exclusive. The possibilities offered by museum archives have been to an extent overtaken and artists, as they reflect on the human condition, will have to look beyond to the challenge of these new sites of culture and the new technologies of the twenty-first century.